Hook, line and TikTok

Can financial advisers reel in Gen Z?

Type “financial advice” into TikTok’s search bar and you are greeted by streams of emoji-laden, fast-paced videos touting trading tips.

Welcome to the subterranean world of financial advice.

From the technicolor feeds of social media 'finfluencers' to the neon corals and electric blues of neobank logos, parts of the financial world have embraced a new, youthful energy.

It is not just aesthetics, these players are eating into advisers’ domain. In the scramble to win over new generations of investors, finfluencers and neobanks are teaching young people how to understand their finances, and advisers need to pivot to keep up.

Financial advisers have never targeted young people.

Only a fifth of the average adviser’s clients are under 45, says St James's Place research. Some argue that is because young people do not have portfolios worth managing, but social media finfluencers and neobanks claim they are better at targeting a valuable market segment that will eventually mature into paying customers.

Advisers should be making more of that market, says adviser Matt Cross of Elmstone Financial Planning.

“Even if they’re not looking to attract a younger demographic [now], these individuals will one day become the chosen demographic. Starting to cater to their ways now is crucial.”

Filling that vacuum are finfluencers, now important contenders for young people’s financial loyalties.

These social media personalities, often unregulated, give out financial guidance for free via apps like Instagram and TikTok, and young people increasingly form their view of the financial world from them, rather than from advisers.

But this could change as some advisers take the plunge into social media.

Alex Stedman, financial planner at Corinthian, has done exactly that, and he has managed to build an audience of more than 50,000.

He films TikToks – short videos – explaining simple bites of information while pacing around his back garden. His videos start disarmingly: a recording sings “bing bang bong” over an intentionally silly picture of himself.

The beauty of it is in appealing to what audiences on TikTok want to see: authenticity and relatability, Stedman says.

“The idea is that you can pick up your phone and just kind of talk to it, and have this scrappy video. When it’s not professional-looking, that’s kind of how the algorithm works: people want to see these interesting things that individuals are doing.”

Stedman started his TikToks during lockdown, when his wife downloaded the app and saw videos from unregulated ‘advisers’ with damaging financial advice gaining traction.

He wanted to help people, he says, and once he took the plunge it “took off so quickly”.

The allure of social media is that young people are able to ask questions “they probably wouldn't dare ask their finance adviser because they're afraid they’d come off as stupid,” says Anna-Sophie Hartvigsen from Female Invest, a financial education platform with a 226,000-strong Instagram following.

“We worked really hard to maintain an approachable brand,” Hartvigsen says of the finfluencing account, and as a result she adds Female Invest gets an “insane” level of engagement.

“When younger people choose who to trust and where to go, it's not about the specific features, it's about the branding. You can get away with having a product that's not even half as good as someone who has the best product in the world, but doesn't speak your language.”

"It’s basic psychology", says Elmstone's Cross, "if someone chuckles at educational content you post on social media, you’ll be more on their mind when they do eventually take financial advice".

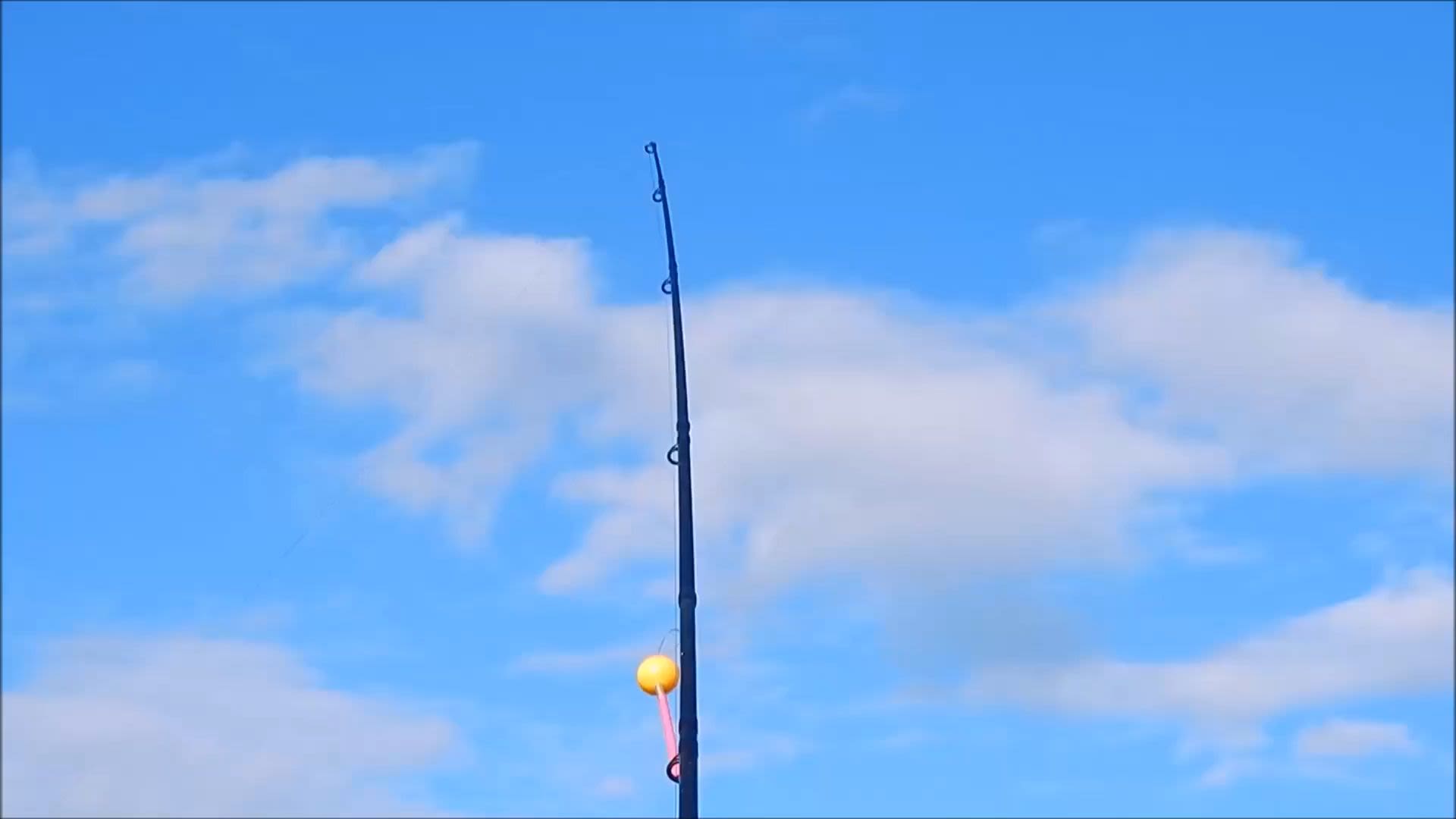

A sample TikTok from regulated adviser Alex Stedman, explaining the concept of compounding, viewed over 630,000 times so far

The challenge: hooking clients of the future

“Young people won't use financial advisers,” says Ryan Lane, consultant at Altus, “though that's not necessarily for want of trying.

"Young people tend to have less money just given the time period that they've been able to accumulate [money in].”

But there is an inflection point at which a young person tips over into needing professional advice, and at that point they usually turn to a friend of a friend, or someone a relative recommends, he adds.

“The stickiness of clients within advice is pretty high. So if you've already got them on that conveyor belt, and have engaged them early… you've got them within the business and within the ecosystem, so it should be easier to turn them into proper clients when required.”

Younger people do want to engage with the financial system, Lane says, but the problem lies with an “opaque” investment industry that has not updated its structure for decades.

Trying to engage younger people with softer educational guidance, rather than transactional advice, is “relatively easy”, he says, but they will not want to read a 25-page glossy brochure: “It needs to be something a little bit more interesting, a little bit more rewarding.”

The ‘neo’ apps going toe-to-toe with advisers

Also taking over the young advice market are neobanks and neotraders.

Popular neobank Monzo, coral-coloured and a staple in young consumers' wallets, has its sights set on becoming a “financial adviser in your pocket”, according to chief operating officer Sujata Bhatia.

The app has been ramping up its financial guidance for a while; its ‘pots’ feature encourages users, with plenty of guidance articles, to set aside spare change each month towards future goals, and the app provides personalised charts to show users how they tend to spend their money each month.

Our goal at Monzo is to be that financial adviser in your pocket.

Neotrader eToro is vying for the young advice market in a different way: it encourages its users to teach and question each other with a scrollable Twitter-like feed in which successful investors explain their strategies.

“We've got this kind of social aspect, which allows and encourages people to share information,” explains UK managing director Dan Moczulski.

The app's sociability even provides a copy-trading mechanism allowing users to look for popular investors and copy them.

"With that kind of initiative, I could say that we go toe-to-toe with advisory firms," Moczulski says.

Powered by gamification

It is powerful gamification that draws people in to apps like these, adding game-like features leverages users’ preferences for fun, sociable interactions to ensure they interact more with their chosen finance app.

eToro’s copy-trade feature is one example, allowing people to copy celebrities’ or friends’ trades almost turns eToro into its own engaging social network, says Altus’ Lane.

To many though, gamification spells controversy. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority has warned consumers away from apps like the now-infamous Robinhood that make trading too game-like.

Features like confetti animations celebrating a stock trade and trader leaderboards are “of concern”, it says.

Gamification definition: using game-style mechanics to incentivise people's engagement in non-game contexts. Source: Investopedia

But “there's absolutely a place for it,” says Lane. Gamification should be a tool to draw people in, Lane adds, and interest them to a degree where they seek advice.

He points to risk-profiler Be-IQ, which uses gamification to drive its signature behavioural insights – successfully, Lane notes.

Be-IQ defends its gamified model on its homepage. “Behavioural measures acquired using gamified assessments can reflect behaviours more accurately than questionnaires,” it says on its website, because game-like interactions reduce fatigue.

Advisory firms can use gamification themselves, particularly when it comes to building smoother onboarding for new, younger users, says Lane.

“[Onboarding] is the most difficult thing. It's fraught with gaps; you have to go back to the client 15 times for different documentation, for wet signatures.”

Firms can create graphics showing progress alongside pop-up informative videos – the opportunity is low hanging fruit, he adds.

But the in-house build of those sorts of technologies tends to be quite involved, and barriers to entry for gamification are high, Lane warns, because not only does it need complex coding, the “magic” lies in the digital engagement being fully linked to the process that sits behind it.

If you look at social influencers, on the other hand, there’s a “super low barrier” to entry, anybody can get involved.

Sample screens from the Monzo app showing colourful, fun engagement techniques.

Sample screens from the Monzo app showing colourful, and fun, engagement techniques.

Sample screens from the Monzo app showing colourful, fun engagement techniques.

Sample screens from the Monzo app showing colourful, and fun, engagement techniques.

Sample screens from the Monzo app showing colourful, fun engagement techniques.

Sample screens from the Monzo app showing colourful, and fun, engagement techniques.

The question remains whether finfluencers are helping people, or merely flogging paid products.

Many finfluencers give out atrocious advice, but many also provide a “really good'' education, Stedman says.

You do not need to be a financial adviser to answer plenty of questions, he points out. And despite brands occasionally sponsoring finfluencers, muddying the waters, it remains “pretty obvious” which items are sponsored. “People aren’t stupid,” he adds.

Finfluencers must now include disclaimers if one of their posts is an ad, and TikTok has banned financial promotions.

The FCA has been active in warning social media creators about making financial ads, enlisting celebrity Sharon Gaffka in April for a campaign about the legalities of financial promotions.

The best thing you can do is get on there and try and counteract it with quality.

Policing promotions will become trickier, however, as social media twines more closely with financial capabilities.

Twitter in April rolled out a bespoke feature that lets users buy and sell stocks and other assets directly from eToro, and the Instagram-based Female Invest has purchased a trading platform of its own, Gaia Investment.

As finance changes, reeling in Gen Z to advice services will not be simple. The waters are teeming with competition.

“There are obviously going to be some people on there that are going to use it for their own selfish means,” says Stedman. “You can’t do much about that I’m afraid, the best thing you can do is get on there and try and counteract it with quality.”